Double Feature: 30-Something Delinquents Going on 16 (Crime in the Streets & The Delicate Delinquent)

Look, I know better than anyone that turning 30 can be rough. All that peer pressure, awkward insecurity, the fights with mom, not to mention the raging post-puberty hormones… Wait did I say 30? I meant 16. Sorry, I get those two confused for some reason. Maybe because according to most movies those two ages are practically interchangeable as far as casting goes. I mean, I get it as far as labor laws and all, but you’d think there’d be more of an effort to keep the ages younger than, er, an age where you could conceivably have your own double-digit-aged child.

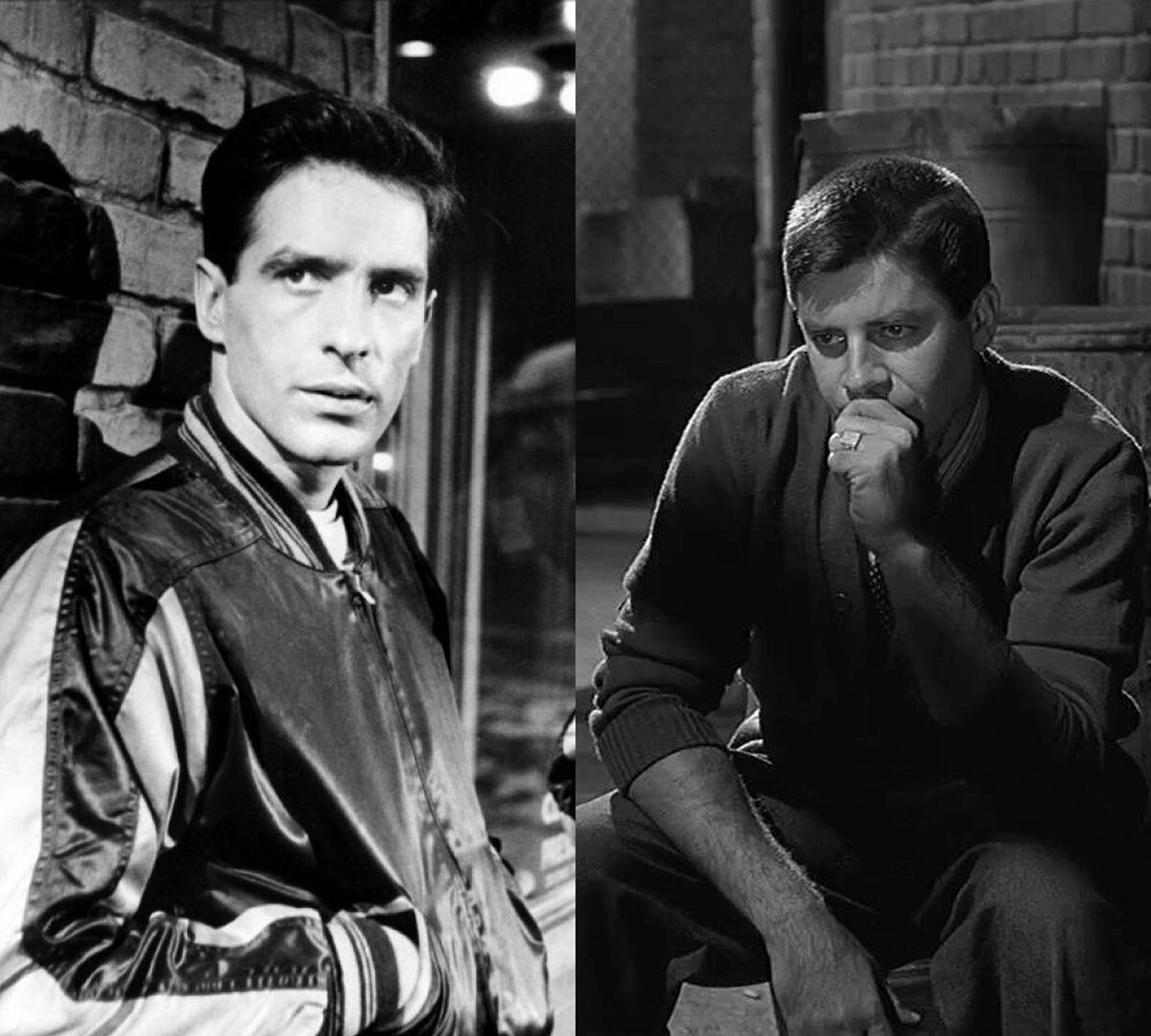

Well, for today’s double feature we are embracing a pair of not-actually-teenage daydreams in two late 1950s films. Not only did both of these movies, released a year apart from each other, feature street-brawling juvenile delinquents who struggle against an empathetic social worker, but they also star famous American auteurs as our main rebels without a cause. That’s right, it’s directorial legend babe John Cassavetes and legendary director doofus Jerry Lewis! I get how a 31-year-old Jerry Lewis got cast, he commissioned the picture and co-wrote the script, but I’m at a bit of a loss for anybody felt 27-year-old Cassavetes fit in with 17-year-old Sal Mineo and comparatively baby-faced Mark Rydell, but who am I to judge. Some people mature faster than others I guess.

Crime in the Streets (1956)

Don Siegel’s Crime in the Streets is about what you’d expect for a ‘50s juvenile delinquent story. It’s the Hornets versus the Dukes, two teen street gangs that have nothing better to do but harangue girls and torture each other. The leader of the Hornets is Frankie (John Cassavetes), our main teen psycho. Armed with menacing glares and a massive chip on his shoulder, he’s completely resistant to the pleadings of his well-meaning social worker Ben (James Whitmore), his shrill single mother (Virginia Gregg) and his younger, innocent brother Richie (Peter J. Votrian). Instead he prefers the company of his doting peers, the emotionally unhinged Lou (Mark Rydell) and wannabe tough guy Angelo, aka “Baby” (Sal Mineo), both of whom he gleefully bullies into doing his bidding.

This New York street gang ecosystem hums along fine until one skirmish gets a little too real too quick and a neighbor, Mr. McAllister (Malcolm Atterbury), calls the cops, resulting in one of the Hornets getting arrested. Frankie (John Cassavetes) is furious and confronts McAllister with all of the pride and rage of teenage psycho egomania. Undaunted by Frankie’s teacup tempest, the middle-aged McAllister pulls rank and slaps Frankie clean across the face–in such a way that you can guarantee the reverberations were heard clear ‘cross town. Frankie, rocked to his adolescent core by this blatant disrespect, decides swift action must be taken while emotions are still running high, and enrolls Lou and Baby to help him up their game to murder.

Look, the plot is insipid and cliched, the set is so clearly built on a Hollywood sound stage, Cassavetes is obviously ten years older than he’s meant to be and the whole film is really just an excuse to both exploit and simplify the real pain felt by broken, poverty stricken homes. But what saves this otherwise bland tale from melodramatic obscurity is the surprising amount of nuance each of our main actors bring to their characters. Cassavetes gives the most gloriously histrionic performance I’ve ever seen him give as a teen who flies into a rage if anybody dares to touch him, where Mark Rydell has the time of his life interpreting “street punk” as ‘open homosexual flirtation with a touch of murderous lust,’ and Sal Mineo does what he does best, rallying or instantly melting as the occasion calls for.

Where the clunky dialogue and fake set keeps trying to pull us back into 1950s cliches, it’s clear from Cassavetes acting that he’s been busy reading between the lines. When social worker Ben tries his best to connect to Frankie through some misguided sense of empathy and duty, spouting armchair psychology about how the reason the teen acts out is just because he requires the love of a nuclear family, Frankie sits there smirking at him sardonically. What easily could have become a stagy teaching moment for the audience suddenly turns dark when Ben reaches out to touch Frankie on the knee and you watch Cassavetes automatically jerk away from his touch. It’s a disarmingly chilling moment that makes you realize Ben doesn’t even know the half of Frankie’s problems, leaving your mind to race with a myriad of horrendous possibilities that could result this type of instantaneous reaction.

Meanwhile, Sal Mineo’s being forced to smoke a used cigarette stub while holding back tears, or avoiding eye contact with his father who’s so at the end of his rope with his troubled son he resorts to beating him. Mark Rydell is over here licking his lips and giggling his ass off at the thought of knifing a guy for kicks, humming his own West Side Story-esque theme song while making eyes at the untouchable Frankie. The three of them together elevate Crime in the Streets to an outstandingly fun watch–especially if you’re into indulging in a bit of the ol’ ultra-violence now and then. For a film that spends a whole lot of time trying to tell you how to feel it sure leaves a ton of leeway to have a ball with its most vicious indulgences. I could have watched an entire TV series on these three.

The Delicate Delinquent (1957)

Now here we are at a very interesting time in Jerry Lewis’ life–and indulge me just a bit if you will because you guys know how much I like to talk about Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. The Delicate Delinquent was originally commissioned by Lewis after somebody turned him on to the legend of Damian and Pythias. No, really. He was so enamored with this legendary tale of male friendship that he handpicked Don McGuire to write a movie that would portray him and Dean in the same way, with perhaps a hope to "fix" their crumbling working and personal relationship. Well, Dean read the script and promptly threw it back in Jerry's face, using an excuse about how he “ran from cops all my life, I'm not about to play one.” But, having seen the film, it's more likely that his anger was directed towards the fact that this was yet another one-sided vehicle for Jerry to hog the lime light for two hours while his character gets little to nothing to work with. While the script itself was hardly the final straw in the matter, the two broke up shortly after and bitterly went their separate ways. Jerry, out of some mix of contracts and spite, went on and made the film anyhow, his first without his former pardner.

Sidney L. Pythias (Jerry Lewis) is a dim but innocent janitor who, through a turn of bad luck, gets mistakenly arrested as a juvenile delinquent. Officer Mike Damon (Darren McGavin) decides to take it upon himself to help this wayward youth, as was once done for him at a decisive crossroads in his youth. He takes the case and is forced to team up with civil servant Martha (Martha Hyer), and mouthy broad, to get the job done. Sidney takes it all in stride and decides now’s a good a time as any to follow his dream to become a cop. Fast forward through several comedic police academy training montages, including one Japanese wrestling montage where Lewis indulges in some of his patented cringe-inducing casual racism, as well as one genuinely fun Theremin-based physical comedy scene, things are largely looking up for little Sidney. That is, until his police-issued gun is used to shoot one of the neighborhood hoodlums and his future as a cop is thrown back into jeopardy. Hey, turns out 1950s cops hold their own accountable for unnecessarily shooting criminals (well, in the movies at least).

I won’t lie to you, I found this to be a largely sappy and joyless story, made worse by the fact that it clearly thinks it has something very important to say. So built up with sentimental fanfare and the weight of this being Jerry Lewis’ woe-is-me new solo gig, it’s frustrating to watch all of this on-screen angst amount to a disappointingly simple one-note toot of "try hard and you'll get places!" Not that any of the previous Martin and Lewis movies had particularly mind-blowing plots, just the opposite, but its attempts at sincerity ring extra hollow when your main character undercuts his own pathos by cutting it with various slapstick jokes.

On the other hand, it’s fascinating to watch these scenes that were clearly written for Dean Martin play out with some stand-in interloper. It’s not that Darren McGavin is bad so much as he’s just pointedly not as charming or funny as Dean Martin. Damon's role is to basically beg Pythias to be his friend, support his every whim, and defend him to the end–aka, quite literally a supporting "stooge" with zero character development. Meanwhile Jerry gives himself the entire emotional heart of the film, including a sappy song he sings to himself alone in an alley, all of the humorous beats and a happy ending on top. Where Crime in the Streets has something sinister bubbling under the surface, this movie is your true 1950s moralistic tripe. The likes of which glosses over reality in favor of wrapping everything up in a neat bow and a stern lesson.

As to be expected in any 1950s’ male bonding film, this movie also sports a weirdly hostile undercurrent towards Martha, its main female character. After this nagging shrew dares to enter this hollowed male space and to tell the men how to do their jobs, she is punished by Damon who, besides verbally berating her, sets her up for failure in a bad part of town in order to teach her a lesson. A brush with powerlessness at the hands of a bad man magically transforms her into Damon’s demure and doting girlfriend. This truce lasts until he tells her she'll never be as important as Pythias or his job. Martha’s whole character is bizarre, and feels more like a stand in for Jerry or Dean’s actual wives than a believable social worker–the "competition" if you will. All in all, where it lacks in sincerity or compelling drama, it’s a out and out Freudian field day of repressed male angst and longing.