What a Twist: Double Consciousness and M. Night Shyamalan

Popular opinion about M. Night Shyamalan is that he started strong, didn't live up to his potential, and then fell off a cliff after The Village (2004)–it’s no coincidence that Robot Chicken’s “what a twist!," sketch came out in 2005. A decade on, though, films like The Visit (2015) and Split (2016) seem to finally be shaking that consensus. This new praise shouldn't fool you, though: no matter his shortcomings, Shyamalan, throughout his entire career, has always had a consistent vision, made coherent through his strong direction and his visual composition.

The first step to understanding his singular vision is to acknowledge that he is not white. Shyamalan is not typically viewed as a minoritized creator, aside from the other popular "joke" about purposefully messing up the pronunciation of his last name. Some of that's the way racism manifests for different groups–the model minority myth, for example–though it's also in part because of his own dissociation from overtly racialized work. Yet (and hopefully without sounding essentialist), pretending that he's uninvolved in these experiences makes his movies appear thinner than they are, rather than bolstering what is great about his work on whole.

As a director, Shyamalan is interested in his actors’ ability to perform with split identities. Whether the setup is a dead man who thinks he's alive (Bruce Willis in The Sixth Sense, 1999), a boy whose desire to escape his father’s shadow is hindered by incredible circumstance (Jaden Smith in After Earth, 2013), or an Indian-American in India trying to figure out his place in either country (himself in Praying With Anger, 1992), the result is, to a greater or lesser extent, the same.

His first film, Praying With Anger, is crucial in understanding Shyamalan's characters. Arguably his only film that doesn’t include overtly supernatural elements, it is also his only film (other than After Earth) that does not have a white protagonist. The ‘twist’ in Praying With Anger, an inverted immigrant narrative, comes in the form of W. E. B. Du Bois' "double consciousness”–the idea that oppressed groups are forced to view themselves through both the eyes of the oppressor as well as their own perspectives.

A film about an ethnic minority, identity and coming of age has a built in dualism that casting white leads doesn't allow for. Instead of abandoning this theme, Shyamalan simply found other ways to channel it: in a thriller (with a twist), even a white man must be (and so act) divided against himself. In that way, the greatest twist of all is that the twist is just a tool, used in order to achieve layers of depth.

The misdirection in Shyamalan's composition tends toward subtlety, with a strong technical bent. In addition to character-based tension buried underneath the plot, he added technically beautiful framing that centers on misdirecting the viewer. The clearest example is in The Sixth Sense when Cole (Haley Joel Osment) steals a Jesus figurine from a church after his second discussion with Malcolm Crowe (Bruce Willis). With his back to the camera, Cole, along with the various figurines and the votive candles, all imply movement toward the top of the frame. While the viewer is watching for Cole to exit, a new composition emerges out of the old. The color pop of the red Jesus figurine is coupled with the new leading line (in the form of the ends of the church pews), making the figurine the center of the shot just as Cole swipes it.

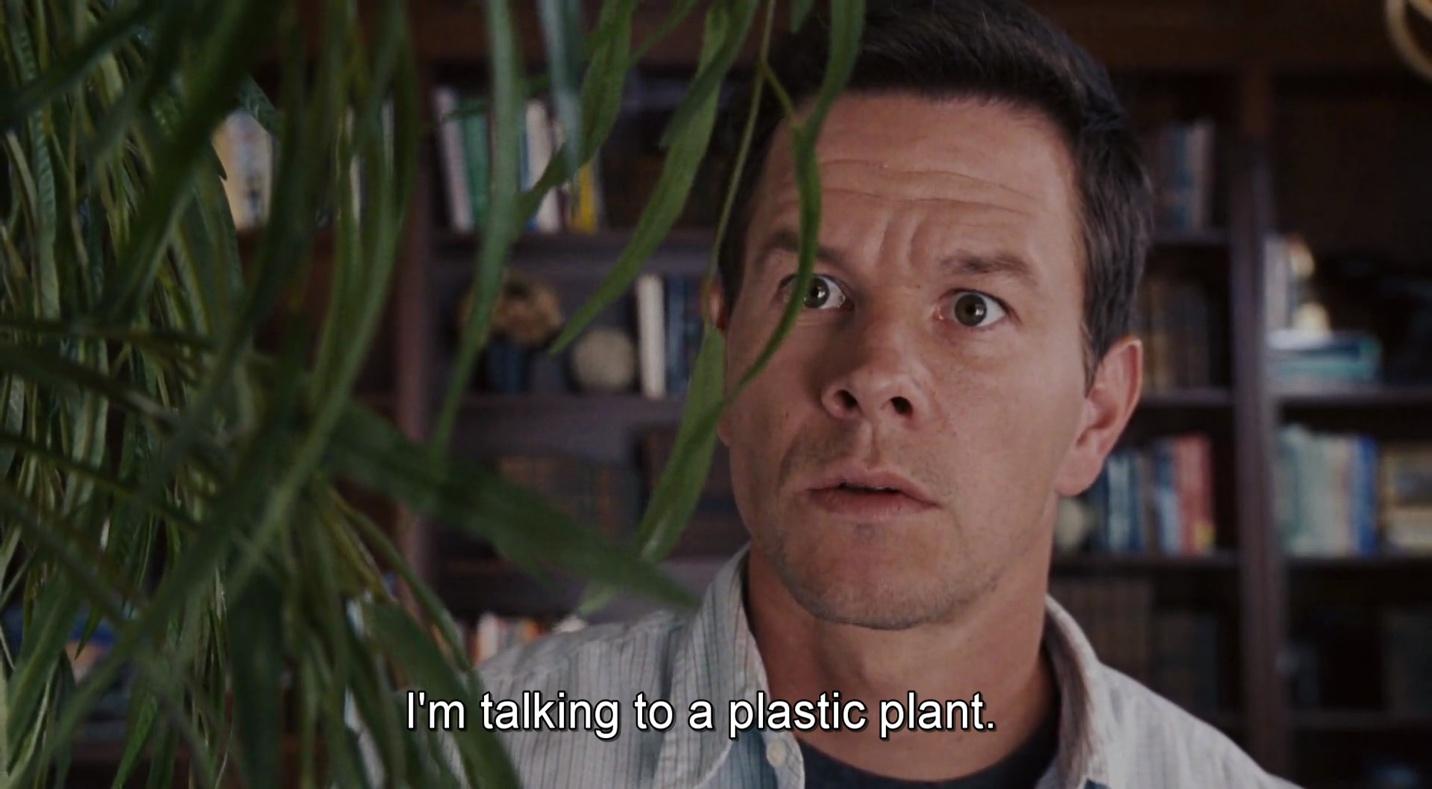

Or take the scene in The Happening where Elliot (Mark Wahlberg) finds himself entreating a plastic plant. It’s an isolated scene, and it almost plays out like a best-of-Shyamalan mini movie. Elliot talks to the plant in reverse shot, as though it were an actor. His approach to the plant is matched by a slow horizontal pan and vertical tracking shot that reframes the shot in such a way that it begins to look like a true interlocutor just before Elliott realizes that it isn't.

The problem is that Wahlberg's (presumed) direction–acting in a way that indicates a thriller version of double consciousness–doesn't match the actual story, where he has known what is (titularly) Happening from the film's half hour mark on. Elliot is, in other words, lacking belief rather than knowledge, and so Wahlberg's stilted performance comes across not as a doubling of his self, but as mere extravagance and overacting.

The concept of the twist being the sole or critical point to an entire film, instead of just a narrative device, is a patronizing interpretation of an entire body of work. Shyamalan’s films explore beauty in underappreciated places, whether he’s focusing on a pervasive sense of fear or perhaps using the lens of the supernatural to shed new light on the ordinary; it’s hard to not see the impact of race on his work. Rejecting Robot Chicken's jokes–that his plots repeat pointlessly, and that his race is so negligible as to be mocked–allows the viewer to see what was always there: a joyous excuse to shoot the most benign landscapes with a malevolence usually reserved for horror, or even just to frame the shitty pool of a run down apartment complex like it's the most beautiful thing in the world.